Never?

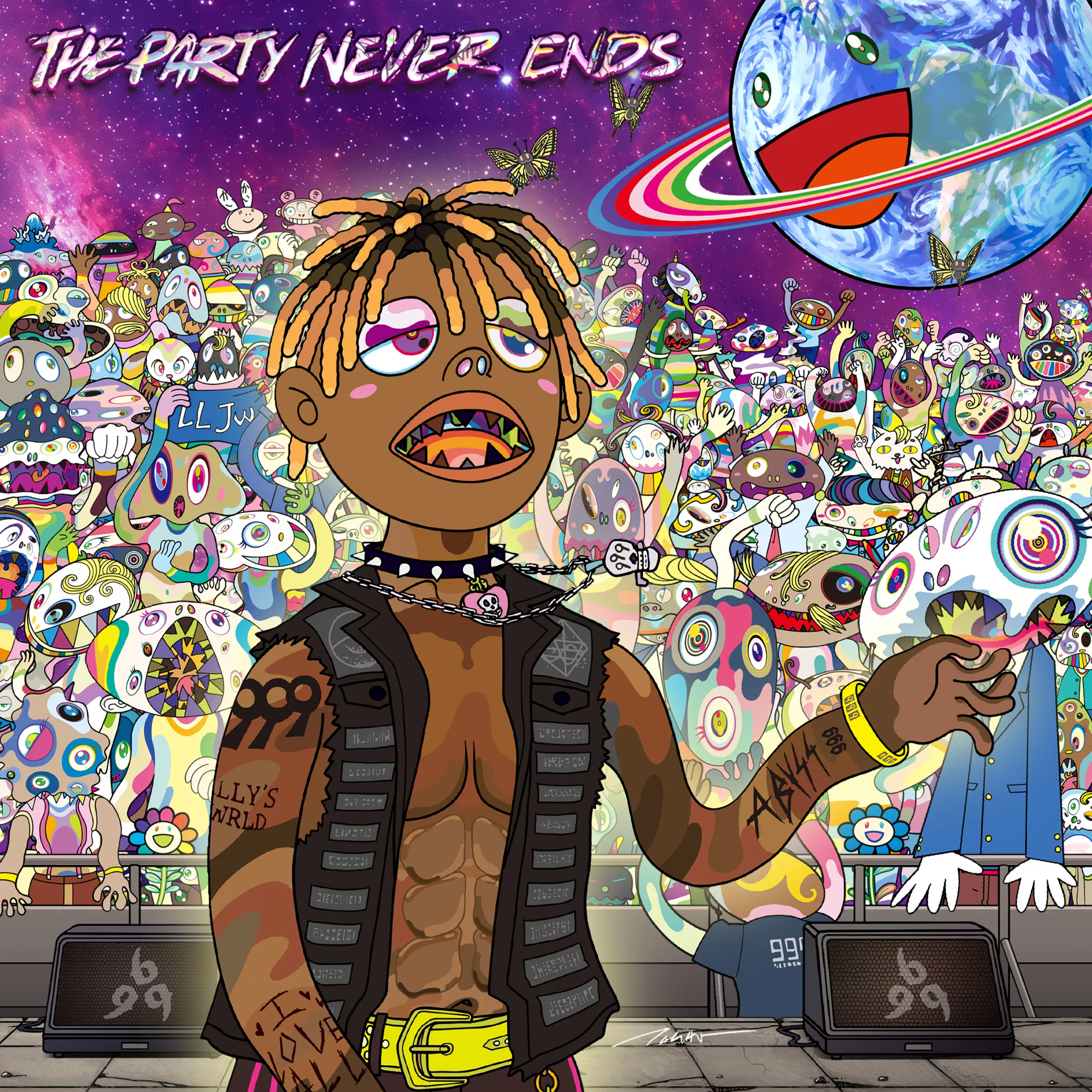

Juice WRLD died of a painkiller overdose on December 9th 2019. Yesterday, almost exactly five years later, Juice WRLD released his new album, The Party Never Ends. Today, a digital recreation of him will perform a virtual concert in children’s video game, Fortnite.

So, this is a review of The Party Never Ends, how was it? Messy, but a fair amount of the tracks came together OK. Fall Out Boy turn up at one point, for some reason.

And with this in mind, I’m giving this album a 5/10.

If that’s all you needed to know, click off now. All the text below here is just this article’s outro.

Posthumous music releases are so totally nothing new, Für Elise was released forty years after Beethoven’s death, and all that. And they’re nothing new for Juice WRLD (real name Jared Higgins) either; this has been his third album since he’s died. Take a moment to decide for yourself how that makes you feel, no wrong answers.

Higgins’ mother, Carmella Wallace, has done all she can to turn her grief into action through setting up the Live Free 999 foundation in her son’s name, raising hundreds of thousands towards mental health and substance dependency causes. Through this, she keeps alive the value her son gave many of his fans, and what his honest and cathartic appraisals of his own struggles meant for them. And moreover, everything done with her son’s legacy has had her stamp of approval. So, we’re all fine then, right?

Pete Jideonwo, Higgins’ manager, said that he was intent that the Fortnite collaboration was “tasteful”. And by all accounts, Higgins did enjoy the game a lot in his lifetime. Let’s stick on that word Pete used there, though. Tasteful. Whenever we talk about this, it always comes back to tasteful, doesn’t it?

It is a clear sign of how little our language equips us for these conversations when tasteful is the main word we have to describe if the continuation of a dead artist’s memory has been done correctly. You might remember tasteful from the last time you saw a set of curtains complement the aesthetics of its room.

Is that what’s at stake when we’re discussing how we shape a dead person’s legacy, aesthetics? What is a good or bad look? No. Even the most atheistic know we all have some sincere concern to how we treat our dead, either in physical remains, or in how they are remembered. Even if we clearly can’t put our words towards why some ways are correct, and some ways are not.

It’s difficult to put exact words to describe why we might feel this all matters. But the inability to find these words allows a fog to be cast over what line we do have for what is right and wrong, and allows those who benefit from nudging the line further and further back to just keep on nudging. Do we even really find a dead guy getting reanimated in Fortnite as shocking as we might have half a decade back? At worst you might find it some level of gross still perhaps, but it doesn’t feel as much of a surprise now, does it. We’re getting a bit more used to death being a commodity.

Walk with me into a dark place, and think like the most cynical record exec you can: Wouldn’t you want your artists dead?

For one, that artist gets a massive publicity boom. The more they were loved by audiences when alive, the greater the emotional leverage you have on them from the loss. Everything they made while alive has been made so much more precious because it has just become finite: all at once, that’s all they ever made.

But what if that finite supply never has to end? What if you can just keep the dead making their art, and even better, unobstructed by all those pains that come with the artist having a say in what they do? Great if they have some old song projects knocking around on a hard drive, but hey, even better, what if death doesn’t have to be a barrier to an artist’s voice singing new words for us?

It’s the worst kept secret that the next frontier for the booming dead artist industry is just how fast we can normalise AI-generating voices. At the minute, none of the public seems warm to it, except the cryptocurrency misanthropes of X Premium. Oh, and all the major record labels who output the likely majority of the music you love, pouring millions into it. It doesn’t get normalised by us becoming happy with it, it will get normalised by us becoming numb to its slow rise, until it’s just how things work now.

No, there is no correct way to tell a mother how they should feel about their son’s death, and their choices. If Juice WRLD’s memory has in some way gotten mishandled here, the blame is not to be put at Carmella Wallace’s feet. Her undoubtable sincerity should not shroud the cynical motives of the many other benefiting parties in our culture, as murky as that becomes to delineate, and as the frog reaches the boil.

Do artists owe us more of their being when they die than everyone else? Well, we already seem to suppose so, but what’s our cut off?

If we decide we want to stop now, our first brakes are what we have to say about it. And right now, the main words used to facilitate what we have to say seem to amount to tasteful, icky, and Black Mirror-y. All facets of death are hard to put words to, but if we don’t really try, then that’s great news for those who profit.

Funerals are for the living, so along with inheritance, the dead gifts them to us.

What other gifts can we decide the dead have for us?